| Previous | Next | |

| Parsing_01_background | Parsing_02_formal_spec | Parsing_03_what_is_parsing |

Parsing: (02) Formal Language Specifications

How do we write the rules of a language? (FSAs, CFGs, etc.)

More on Parsing:

- Parsing: (00) Some sample code to refer to—Some code you can run, compile, and consult as go through the tutorial

- Parsing: (01) Background—What is this parsing stuff all about?

- Parsing: (02) Formal Language Specifications—How do we write the rules of a language? (FSAs, CFGs, etc.)

- Parsing: (03) What is parsing?—The general and specific sense of the word, and explanation of three phases: tokenization, parsing, evaluation

- Parsing: (04) Tokenization—Context Free Grammars, EBNF, and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Parsing: (05) Parsing, Grammars and ASTs—Context Free Grammars, EBNF, and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Parsing: (06) Evaluation Phase—The specific phase where we apply grammar productions and construct an AST

- Parsing: (07) Syntax vs. Semantic Errors—The formal definition of the difference

Acknowledgments: this series or articles is joint work, a collaboration between Kyle Dewey and Phill Conrad.

Formal Language Specifications

Before you can write code to tokenize, parse, and interpret, we need a set of rules for the language. Here’s how those rules are typically provided to you:

- Tokenization: The legal tokens of the language are typically expressed as

- A set of legal input characters (the alphabet of the language)

- A finite state automaton (or equivalent formalism) the specifies the legal tokens

- Parsing: The syntax rules for parsing the language are typically expressed using a context-free grammar.

- A context free grammar, abbeviated CFG is often just called the grammar for the language (the “context-free” part being implied).

- We’ll cover CFG in more detail later, but as a summary: A CFG consists of a set of terminal symbols (corresponding to tokens), non-terminal symbols, and productions.

- There are various ways of expressing a CFG, one of which is Extended Backus Naur Form (EBNF), which we’ll also cover in more detail later.

- Evaluation/Translation: the semantic rules of the language cover how to produce this thing called an Abstract Syntax Tree, and what to do with it.

- Sometimes they are specified entirely informally in natural human language (usually English). This can be dangerous, since human languages are notorious for their ambiguity. Indeed, this ambiguity is where many real world compiler bugs and inconsistencies arise. *These occasionally lead to security vulnerabilities.)

- Another option is full-on, rigorous formal specification using the language of discrete math: set notation, logic, etc. i.e. , the toolsyou learn about in courses such as CMPSC 40, and CMPSC 138 (ah, now you know what those courses are for. :-) ). The advantage is that this method typically means that the language so specified has a formal, precise, unambiguous meaning about which theorem’s can be proved. A few disadvantages are that relatively few people are comfortable enough with this notation to accurately translate it into code, and that often, it can be quite complicated to express even the simplest of concepts with total rigor.

- The common case is usually a middle ground, in which formal notation is used for some aspects of the language, and informal specification for others. Of course, like most compromises, this incorporates both the best and worst features of the two extereme options above.

Example Formal Rules for Tokenization: A Finite State Automaton

The rules for tokens are typically expressed as a finite state automaton.

- Other names: finite state machine, finite automaton (the “state” is implied)

- Finite state automata is the plural form (the “a” at the end is the plural form in Greek, automaton being a word borrowed into English from Greek.)

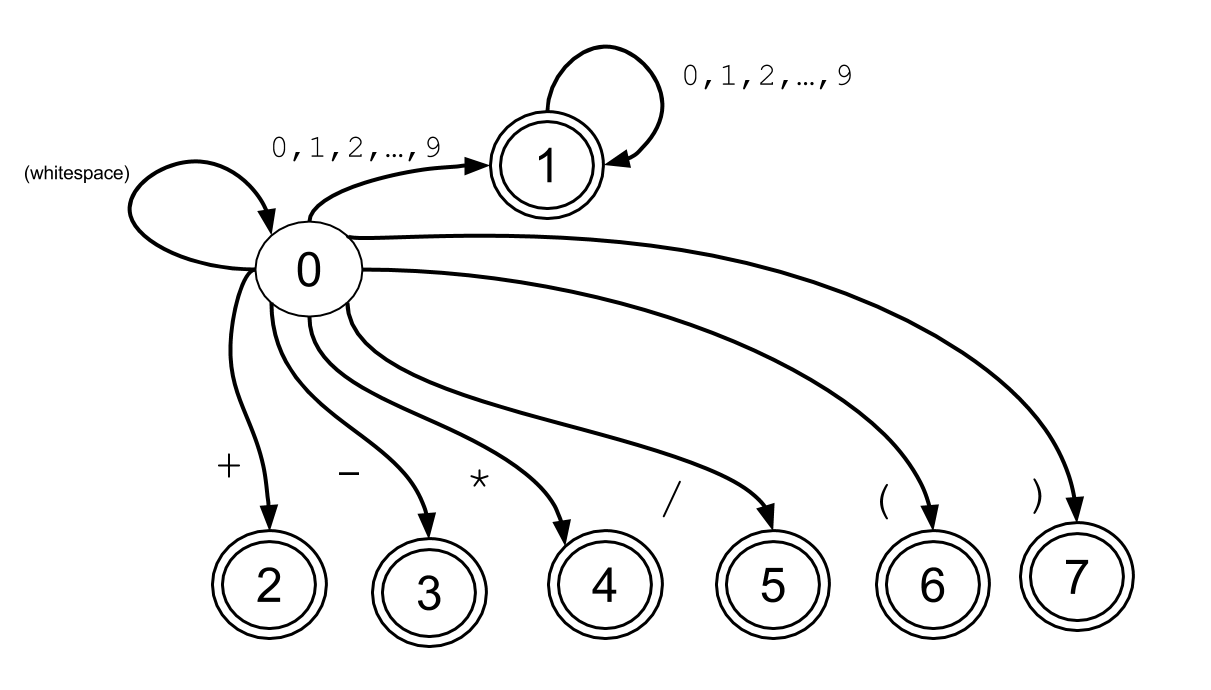

Here is a finite automaton that corresponds to the tokens in our language:

In this diagram, circles represent states. In the diagram, the states are labelled with numbers. We’ll refer to the state labelled with 0 as state 0, or simply s0. Similarly, we can refer to s1, s2, etc.

In a finite state machine, the number of states is always finite. That’s where the machine gets its name. So, we typically label the n finite states with the sequential integers 0 through n-1, though that’s only a convention. We can actually label them any way we want.

There are two special kinds of states:

- In this diagram, the circled labelled

0is, by convention, the start state. The machine always starts in this state. - The double circles are accepting states. When the machine is in one of these states, if the end of the input is reached, we say that the machine has accepted a string in the language. Our language is this case is the language consisting of acceptable tokens, which includes integers, the operators

+,-,*,and/, and the two paren characters(and).

You can have non-accepting states other than the start state. Although in this diagram, the only non-accepting state is the start state, that would not have to be the case. We’ll see examples of a non-accepting state that is not the start state later when we discuss how to handle tokens such as == and !=.

Transitions: Each arrow from one circle to another represents a transition from one state to another. Typically, a transition requires us to read a character from the input (unless we allow lambda/epsilon transitions; see below). The transitions are labelled with the character that we must read from the input in order to move from one state to another.

Multiple labels on a transition are a shorthand for multiple transitions. In some cases, e.g. the transition from s0 to s1 in this machine is labelled 0,1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. That is a kind of shorthand; in fact, there are 10 different transitions, each representing one of those characters. Putting all ten of them would make the diagram much more cluttered, so we typically don’t write it that way, but formally, there are actually 10 different transition arcs from s0 to s1 in this fsa.

Lambda transitions (Also called epsilon transitions). Typically you can’t move from one state to another without consuming a character from the input. Sometimes it is convenient to allow a transition without reading a character. These transitions are labelled with a special character representing the empty string. Depending on the author/professsor, this character may be:

- uppercase Greek lambda (Λ),

- lowercase Greek lambda (λ)

- lowercase Greek epsilon (ε)

The choice of letter is aribtrary.

How we use lambda transitions: In our case, we might consider that there is a transition on Λ (upper case lambda) from every state back to the start state that is used if/when there is no other choice we can make. If this transition goes from an accepting state, then we accept the token we’ve read so far. If it goes from a non-accepting state, then we can emit an error token for any characters we’ve read, or just throw an exception indicating we read a bad token.

Other kinds of unwritten transitions In addition to the lambda transitions, we might consider that in the start state, we have an unwritten transition for every character that does not otherwise have a transition. Those transitions would represent the case where we see an illegal character in the input and want to emit an error token to signal this.

Representing the finite automaton in code

The finite state machine shown in the previous diagram corresponds to the code that can be found in the F16 lab06 starter code, in the file Tokenizer.java, lines 31-55

We can see, for example that the circles correspond to calls to the addState method:

fsa.addState(0);

fsa.addState(1, s -> new IntToken(s) );

fsa.addState(2, s -> new PlusToken() );

fsa.addState(3, s -> new MinusToken() );

fsa.addState(4, s -> new TimesToken() );

fsa.addState(5, s -> new DivideToken() );

fsa.addState(6, s -> new LParenToken() );

fsa.addState(7, s -> new RParenToken());

The code above is the code as it appears in the F16 lab06 starter code. Note that subsequent to publishing the starter code, your instructor realized that there was an opportunity to use the Factory Object (DefaultTokenFactory) to remove the dependency on the concrete product classes for the tokens. So, a better way of writing this code, is arguably:

fsa.addState(0);

fsa.addState(1, s -> tf.makeIntToken(s) );

fsa.addState(2, s -> tf.makePlusToken() );

fsa.addState(3, s -> tf.makeMinusToken() );

// etc...

The transitions (the lines with arrows going from state to another, labelled with the character for the transition) correspond to the calls to the addTransition method. Note that the lines labelled with multiple characters, e.g. 0,1,2,...9 are actually a shorthand for multiple transitions. We handle that in the code with a for loop that

makes multiple calls to addTransition:

fsa.addTransition(' ',0,0);

fsa.addTransition('\t',0,0);

fsa.addTransition('\n',0,0);

fsa.addTransition('\r',0,0);

for (char c='0'; c<='9'; c++) {

fsa.addTransition(c,0,1);

fsa.addTransition(c,1,1);

}

fsa.addTransition('+',0,2);

fsa.addTransition('-',0,3);

fsa.addTransition('*',0,4);

fsa.addTransition('/',0,5);

fsa.addTransition('(',0,6);

fsa.addTransition(')',0,7);

Extending the finite automaton to recognize new kinds of tokens.

To be able to recognize new tokens, we may need to add new states and transitions to the fsa. Here is a version of the fsa where we have extended it to also recognize three additional tokens:

- the

==token - the

<token - the

<=token

Note that after recognizing the first = sign, we are in state 8, which is NOT an accepting state (this is shown by the single circle rather than the double circle). That means that if we see any character next other than the expected one, which is a second = sign, we will emit an instance of ErrorToken and go back to the start state.

Each state transition can only handle a single character. So for multiple character operators such as ==, <=, **, etc. you will need multiple transitions, and possibly multiple states. In the diagram above, you see that we have added four additional states (8,9,10,11) and four additional transitions to support the == and <= operators.

In the code, we would represent that with additional calls to addState and to addTransition. Here are examples of those calls.

fsa.addState(8); // a non-accepting state, so we only pass in the state number

fsa.addState(9, s->tf.makeEqualsToken());

fsa.addState(10, s->tf.makeLessThanToken());

fsa.addState(11, s->tf.makeLessThanOrEqualsToken());

fsa.addTransition('=',0,8);

fsa.addTransition('=',8,9);

fsa.addTransition('<',0,10);

fsa.addTransition('=',10,11);

Determining the remainder of the states and transitions is part of your work as a student. You are encouraged to actually draw a diagram to plan out your states and transitions. You do not need to turn in your diagram, but you are encouraged to have one.

How do the finite automata we are looking at related to Mealy and Moore Machines?

If you’ve never heard of Mealy and Moore machines, don’t worry about this section. If you have, here’s how to relate what we are doing to what you already have learned, or are learning.

-

Moore Machines are finite state automata that generate output based on the state they are in. The finite automata we are considering are not exactly equivalent to Moore Machines, even though we are labelling states (accepting states) with output tokens. The reason is that in our case, we are not output the token associated with the state unless we have run out of acceptable transitions to make (i.e. when we find that there is no “legal” transition based on the current input.)

-

Mealy Machines are finite state automata that optionally “emit” output with each transition. The finite automata we are considering can be considered Mealy Machines, in that they “emit” tokens on the transition from an accepting state back to the start state.

Formal Rules for Parsing

For parsing, formal rules are specified in the form of grammars. Grammars are expressions of the rules of a language. A particular kind of grammar is called a “context-free grammar (CFG), and that’s the kind we are going to need to do parsing.

We won’t give a formal definition of what a CFG is since that’s a topic for CMPSC138. Instead, we’ll provide a “good enough” definition for what we’ll be doing with CFGs in this course. We’ll mostly do that by just giving examples, and explaining how to use those examples, rather than dwelling too much in the theory. You’ll get plenty of the theory in CMPSC138, CMPSC160 and CMPSC162.

One way of expressing a CFG is with a notation called Extended Backus-Naur Form (EBNF). Here’s the EBNF for a grammar for simple arithmetic expressions with +,-,*,/, integers, unary minus, and parentheses:

expression ::= additive-expression

additive-expression ::= multiplicative-expression ( ( '+' | '-' ) multiplicative-expression ) *

multiplicative-expression ::= primary ( ( '*' | '/' ) primary ) *

primary ::= '(' expression ')' | INTEGER | '-' primary

The EBNF notation above is used when grammars are represented in plain text files. When we have the freedom to use any symbols we want, grammars are sometimes also represented with a more compact, but equivalent mathematical notation. Here’s the same grammar in that style:

If this is your first time seeing a context-free grammar for a language, this may look bewildering and confusing. If so, be patient—there is more explanation in Part 5 of this tutorial.

There are various forms of CFGs, and getting into that is beyond the scope of this course. For our purposes, it is enough to say that certain forms of CFGs can be converted into a type of parser known as a Recursive Descent Parser. This conversion is fairly straightforward and intuitive, and is also covered in Part 5.

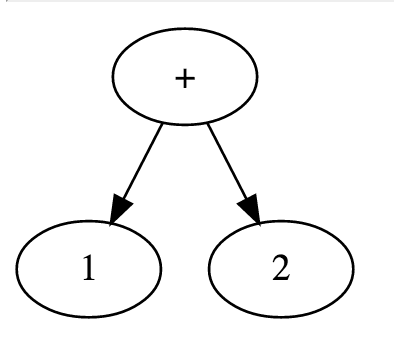

Formal Rules for ASTs

The Abstract Syntax Trees (ASTs) for this assignment are in the form of trees, where each parent node represents an operation, and the children represent the operands. Binary operators have two children, and unary operators have a single child. All of the leaves in an AST for this assignment should be literal ints. By doing a post-orderal traversal of the tree, you can evaluate each of the results (bottom up), and arrive at the result of the entire expression.

This shows an AST which resulted from parsing the tokens 1, +, 2:

As shown, + forms the root of the tree, and it has the child nodes 1 and 2.

Each of these is a leaf, which makes sense considering that integer constants simply evaluate to themselves without any other bits of code getting involved.

Here is one more example:

Here’s an AST for 2+3*5. Note how the tree reflects the operator precedence.

How do the FSA, the CFG and the AST all fit together?

The whole rest of this tutorial will explain this all in much more detail. For now, it is sufficient to get this basic idea:

- We start with a string, e.g. in Java, an instance of

Stringsuch asString input="2+3*5"; - We tokenize based on a finite state automaton to convert that

Stringinto a sequence of tokens, e.g. in Java, an instance ofArrayList<Token>. Those tokens in this example are *IntToken("2"), PlusToken(), IntToken("3"), TimesToken(), IntToken("5") - We parse based on the rules of a Context Free Grammar (CFG), converting that

ArrayList<Token>into an AST, e.g. the image here: - We interpret the AST by doing a post-order traversal of the tree, computing the result of each subtree (bottom up) by applying the operator in the root of the subtree to the operands in the children.

More on Parsing:

- Parsing: (00) Some sample code to refer to—Some code you can run, compile, and consult as go through the tutorial

- Parsing: (01) Background—What is this parsing stuff all about?

- Parsing: (02) Formal Language Specifications—How do we write the rules of a language? (FSAs, CFGs, etc.)

- Parsing: (03) What is parsing?—The general and specific sense of the word, and explanation of three phases: tokenization, parsing, evaluation

- Parsing: (04) Tokenization—Context Free Grammars, EBNF, and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Parsing: (05) Parsing, Grammars and ASTs—Context Free Grammars, EBNF, and Abstract Syntax Trees

- Parsing: (06) Evaluation Phase—The specific phase where we apply grammar productions and construct an AST

- Parsing: (07) Syntax vs. Semantic Errors—The formal definition of the difference

| Previous | Next | |

| Parsing_01_background | Parsing_02_formal_spec | Parsing_03_what_is_parsing |